Enkomi

A pivotal Late Bronze Age urban center on the eastern coast of Cyprus, known for its role as a major copper export hub, its rich material culture, and the earliest use of script in Cyprus.

The archaeological site of Enkomi, situated in eastern Cyprus, approximately seven kilometers north of modern Famagusta, stands as a pivotal Late Bronze Age urban center on the island. Its significance to Cypriot archaeology and the broader Eastern Mediterranean stems from its prolonged occupation, its role as a major copper export hub, and its rich material culture reflecting extensive international connections and the earliest use of script in Cyprus. While often debated in its specifics, Enkomi’s archaeological record provides fundamental insights into the sociopolitical and economic dynamics of ancient Cyprus, making it a crucial site for understanding the Late Bronze Age (LBA) and the transition into the Iron Age. For those unfamiliar with the site, understanding its history, its material wealth, and the challenges of its excavation provides a comprehensive perspective on its enduring importance.

Geographical and Environmental Nexus

Enkomi’s strategic location on the eastern coast of Cyprus was integral to its prosperity. It lies within an area of Quaternary deposits, comprising gravel, sand, silt, and clay. Crucially, the site's southern edge was traversed by the Pedhieos River. During the Late Cypriot period, this river was likely active as a sailing channel, facilitating maritime connections between the coast, Enkomi, and potentially further inland areas. The Pedhieos river drainage system encompassed the Mesaoria plain, the southeastern Kyrenia terrain, and the northeastern slope of the Troodos massif. The presence of sedimentary rocks across the Mesaoria terrain suggests the Pedhieos River was the primary conduit for volcanic rocks and their derived minerals to the Enkomi area. This geological context hints at the significance of local resources and trade routes, particularly the movement of copper from the Troodos foothills. The composition of Enkomi's ceramic and textual evidence often indicates a mixture of marl with well-sorted sand, consistent with the riverine environment.

A Century of Excavation: Unveiling a Complex Past

The archaeological exploration of Enkomi has been extensive, yet complex, marked by varying methodologies and interpretive frameworks over more than a century. Initial excavations began in the early 19th century by antiquarians from Western Europe, primarily focused on Classical antiquity and Mycenaean remains. These early endeavors, however, were often characterized by a lack of systematic documentation, leading to a loss of crucial contextual information.

A significant phase began in 1896 with the British Museum expedition, which unearthed approximately 100 tombs. The excavators, in line with the practices of their time, aimed to collect a "representative sample of the more 'important' finds," with a strong bias towards Mycenaean pottery and other valuable objects, often at the expense of comprehensive recording. This early work led to the initial, incorrect assumption that the Enkomi settlement was located separately from its cemetery. The British Museum's online catalogue now provides a valuable resource for re-contextualizing these early finds.

The Swedish Cyprus Expedition, led by Einar Gjerstad in 1930, further uncovered 28 tombs. While marking an advance in archaeological standards for Cyprus, they initially continued the belief of a separate settlement, focusing on tombs rather than architectural remains.

It was the French mission, under the direction of Claude F.A. Schaeffer, which began in 1934, that finally clarified the relationship between the burials and the living areas, establishing that the town and its cemetery coexisted. Schaeffer's campaigns, which continued until 1974, also brought to light important industrial establishments, particularly those specialized in copper and bronze working, suggesting a continuous metal industry from the Late Middle Bronze Age into the Early Iron Age. However, a large corpus of metal objects and other finds from the French excavations remains unpublished.

Porphyrios Dikaios, Director of the Department of Antiquities, led a joint Cypriot-French expedition from 1948 to 1958, conducting intensive exploration in specific areas (Areas I and III) and excavating 30 additional tombs directly associated with settlement levels. His meticulous documentation and comprehensive publications provided the most detailed stratigraphic information available for Enkomi, significantly enhancing understanding of the site's development and the relationship between its architecture and mortuary contexts.

Despite these extensive investigations, challenges remain. The top layers of the site have been disturbed by agricultural activities, and later deposits have often been obscured by the emphasis on the Late Bronze Age material. The physical state of the site today, described as an "abandoned archaeological park" with eroded trenches and overgrown vegetation, underscores the need for preservation and public access initiatives. Furthermore, the historical interpretations of Enkomi's finds have sometimes been influenced by nationalistic narratives, particularly regarding the "Greekness" of the island based on Mycenaean material, a perspective that modern scholarship re-evaluates.

Phases of Occupation and Urban Development

Enkomi's occupation sequence spans several centuries, primarily within the Late Bronze Age, exhibiting architectural, technological, and cultural shifts. The earliest excavated architecture, found in Area I (Level I), consists of a three-winged building constructed in a modified bedrock depression, with two use phases (Levels IA and IB) dating to LC IA1 and LC 1A2. Notably, both the "vestibule" (Room 119) and "main hall" (Room 135) of the North Wing contained infant remains deposited with pottery vessels, indicating structured deposition practices from the earliest phases.

The ceramic assemblage from these early levels includes Proto White Slip (PWS), White Slip I (WS I), Base Ring I (BR I), Red Lustrous Wheel-made (RLW-m), Black Lustrous Wheel-made (BLW-m), Monochrome, and White Shaved wares, alongside Middle Cypriot (MC III) wares. The transition from PWS to WS I is evident at Enkomi, although it was not a primary center for PWS production, and this ware is largely absent from its tombs. The continuous presence of these wares, including WS II in later Level IB, indicates a relatively swift ceramic evolution within Level I, suggesting an occupation period of approximately 100-150 years.

Level IIB at Enkomi, attributed to the LCIIC period, represents a flourishing era characterized by active trade relations with the Aegean and the Levant, and significant metallurgical production. The pottery repertoire of this period predominantly features local Cypriot Wares, such as White Slip, Base Ring, Monochrome, White Shaved, Bucchero Handmade, and Red Lustrous Wheel-made, alongside Mycenaean IIIB pottery. This period concluded with a widespread destruction and fire event across the site.

The subsequent Level IIIA is marked by a notable shift in architectural style, with the appearance of ashlar blocks in construction. The "Ashlar Building" of this period featured a central tripartite megaron surrounded by rooms. Fortifications were strengthened, and structures rebuilt. While local wares continued, their proportion diminished, and Mycenaean IIIB pottery, including "Rude Style" kraters, persisted. A distinctive feature of Level IIIA is the significant presence of Mycenaean IIIC1b ware, accounting for 42% in Area I and 46% in Area III, along with a smaller quantity of Myc.IIIC:lc. This ceramic evidence, particularly the appearance of Mycenaean IIIC1 pottery in destruction layers, has been interpreted by some as indicative of the arrival of Achaean colonists from Greece.

The chronology of destructions at Enkomi and the identity of those responsible have been subjects of considerable scholarly debate. Similar destructions occurred at other Cypriot sites like Kition, Sinda, and Maa, possibly linked to the widespread unrest caused by the "Sea Peoples" around the time of Ramesses III (c. 1198-1196 BC).

Despite these upheavals, occupation at Enkomi continued into the 11th century BC, albeit potentially on a reduced scale. The site was replanned and rebuilt after the initial 13th-century B.C. destruction, but later phases, particularly in the 11th century, saw minimal architectural renovations. By approximately 1050 BC, Enkomi was finally abandoned. This abandonment saw the urban center gradually move to Salamis, located two kilometers to the southwest, which subsequently became the predominant kingdom on the island during the Iron Age. However, evidence suggests cult continuity in the vicinity of the "Ingot God" sanctuary and in some domestic quarters into the Cypro-Geometric period, indicating a more gradual transition rather than an abrupt cessation of activity. Even after the main settlement was abandoned, terracotta figures from the Geometric and Archaic periods continued to be placed at the site, hinting at its enduring significance as a sacred location.

Economic Powerhouse and International Connections

Enkomi's preeminence in the Late Bronze Age was fundamentally tied to its role in the copper industry and its extensive international trade networks. The site served as one of the main export ports for Cypriot copper, with significant metallurgical remains evident from its earliest phases of occupation. This engagement in global exchange resulted in considerable wealth for the elites of Enkomi and a notable influx of foreign prestige goods, primarily from Egypt, the Near East, and the Aegean.

The material record vividly illustrates these connections. A prime example is a magnificent gold pectoral, an Egyptian "broad collar" (wesekh), recovered from Tomb 93 at Enkomi. This piece of jewelry, emblematic of Egyptian royalty and nobility, is unique outside Egypt, underscoring the deep appreciation for Egyptian culture among Cypriot elites and the far-reaching nature of their contacts. Other bronze objects discovered, though heavily corroded, show prototypes from both the Levant and Egypt, further emphasizing the close interrelations of Cyprus with these regions around 1200 BC.

Mycenaean pottery is particularly abundant at Enkomi, especially Mycenaean IIIB Pictorial Style vases decorated with human and animal scenes, which were produced on the Greek mainland and exported to Cyprus around 1300-1250 BC. These kraters, often bearing signs in the Cypro-Minoan syllabary, are considered major status indicators and point to significant cultural interaction with the Aegean. Beyond fine wares, coarse ware vessels like pithoi, used for bulk storage of foodstuffs, were also part of the movement of goods both within Cyprus and across the wider Eastern Mediterranean, as revealed by archaeometric analyses.

A distinctive feature of Enkomi is the substantial corpus of Cypro-Minoan writing. It is the site with the highest concentration of Cypro-Minoan inscriptions, yielding the earliest known examples ("Archaic CM") and being the sole location on the island where Cypro-Minoan tablets have been discovered. These tablets, such as the one with the 41-41-97 sequence, are believed to be administrative documents, suggesting a complex bureaucratic system. While Enkomi's centrality in the history of Bronze Age writing on Cyprus is clear, it is important to note that petrographic analyses of some "Alashiya tablets" (letters from the king of Alashiya to the Egyptian pharaoh Amenophis IV) indicate they were made from clay not found in the Enkomi region but rather in areas closer to the southern borders of the Troodos massif. This suggests that while Enkomi was a crucial center, it may not have been the sole administrative or "capital" power controlling the entire island, as other hypotheses favor centers in the Kouris and Vasilikos valleys, such as Kalavasos-Ayios Dhimitrios and Maroni-Tsaroukkas.

Social Organization and Mortuary Practices

The archaeological record at Enkomi provides insights into the social organization and mortuary customs of its Late Bronze Age inhabitants. The presence of intra-settlement cemeteries distinguishes Enkomi from earlier Bronze Age practices of separate burial grounds. A variety of tomb types have been identified, including common rock-cut chamber tombs, as well as more elaborate ashlar-built tombs, tholos tombs, shaft graves, pit graves, and even infant burials in pots. The ashlar masonry observed in some tombs may represent an early application of this monumental building technique, potentially predating its widespread use in secular architecture.

Reconstructing mortuary practices in detail is challenging due to centuries of tomb reuse, looting, and inconsistent excavation methods in the past. However, studies focusing on well-preserved tombs and specific burial assemblages have shed light on funerary ideology. The presence of Mycenaean pictorial kraters, for example, has been interpreted as an indicator of high social status. The disposition of prestigious imported goods in tombs, such as the Egyptian broad collar, also speaks to the social power and "cultural biographies" of these objects, how they were valued and integrated into Cypriot elite identities even after their "lives" in their place of origin. The variability in grave goods, from rare and elaborate items to more common locally made pottery, reflects social differentiation within the Enkomi community. Some tombs show evidence of complex secondary burial treatments, including deliberate disinterment and relocation of human remains and grave goods, a suggesting multi-phase ritual systems.

Cult and Ritual Landscape

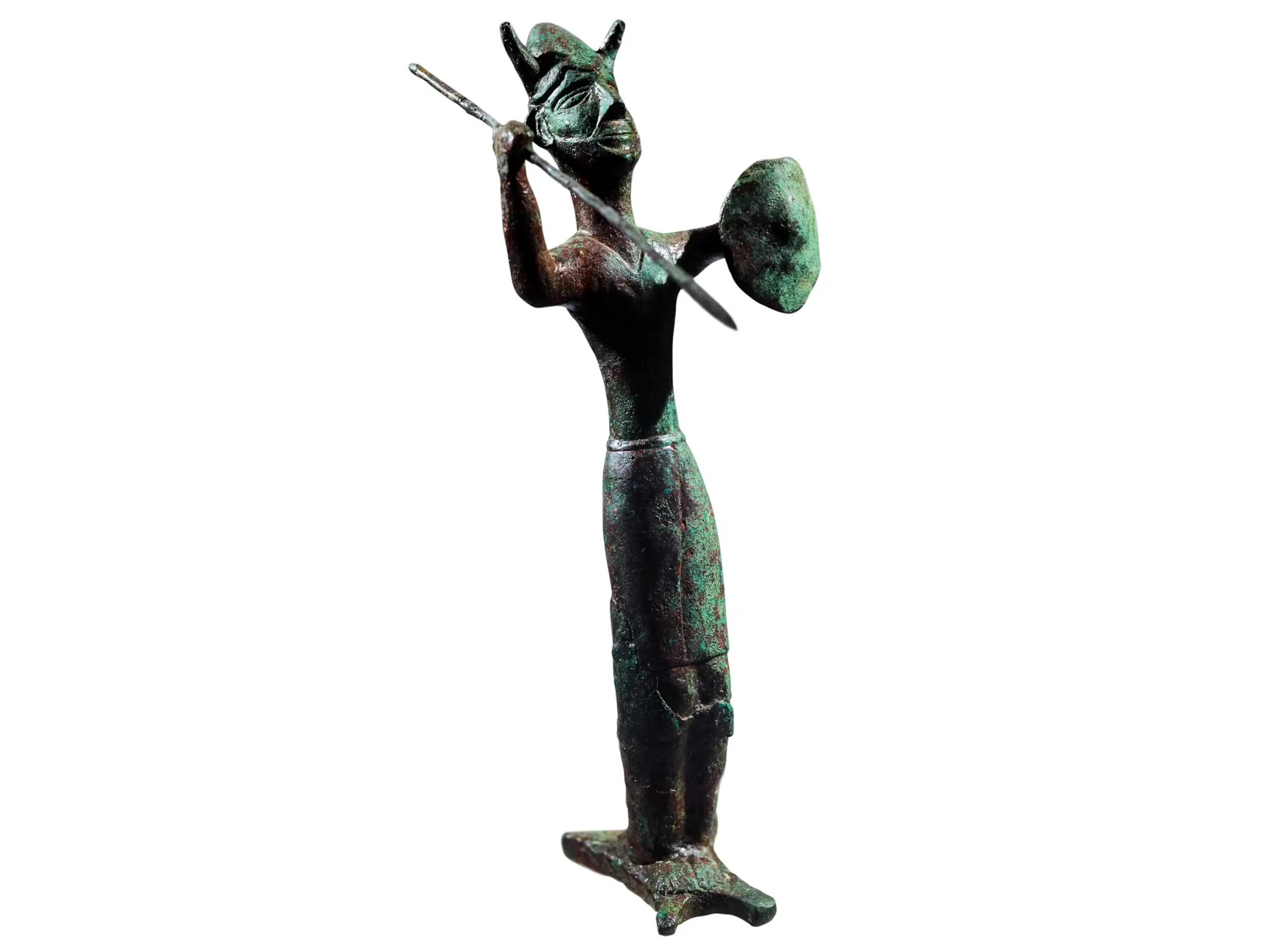

Enkomi’s religious life is attested by several significant cultic spaces and artifacts. The "Sanctuary of the Ingot God" is a prominent example, showcasing continuity of cult activity from its construction phase. The sanctuary, built atop an earlier cult area, yielded an impressive bronze statuette of a deity standing on a copper ingot, alongside a wealth of other objects. Archaeological evidence, including nearly a hundred bull and other bovid skulls with horns, points to a strong bull cult associated with this sanctuary. The presence of "goddesses with upraised arms" terracotta figurines from this area further attests to the diversity of cultic practices. The architectural style of the sanctuary, employing large ashlar blocks for its lower part and plaster-covered bricks for the upper, is similar to other monumental buildings at Enkomi, suggesting they may have functioned as palaces or administrative centers where elite authority was legitimized through ceremonies and rituals.

Beyond the main sanctuary, evidence suggests cultic activity continued in other areas, even after the decline of the city. An extra-urban shrine developed above the abandoned fortification wall during the Cypro-Geometric III and Cypro-Archaic periods, where terracotta figures continued to be deposited, underscoring the enduring sacred significance of the site long after its primary occupation.

Decline and Successor

Enkomi’s prominence as a Late Bronze Age center eventually waned. While largely deserted by the end of the Late Bronze Age, it was not abruptly abandoned. The city experienced replanning and rebuilding after the destruction at the end of the 13th century BC, coinciding with the conjectured arrival of Achaean colonists. However, subsequent renovations in the 11th century BC were minimal. The site's final abandonment around 1050 BC led to the rise of Salamis, a new urban center founded two kilometers to the southwest. Salamis, built on the coast near the Pedhieos estuary, inherited Enkomi's crucial access to the sea and its strategic position, eventually becoming the most important Cypriot kingdom in the Iron Age. Despite the shift of the primary urban center, cultic continuity persisted in the vicinity of the Sanctuary of the Ingot God and in some domestic quarters into the Cypro-Geometric period. The ashlar masonry common at Enkomi may have even influenced the impressive stonework seen in the Royal Tombs of Salamis.

The ongoing archaeological inquiry at Enkomi, despite the site’s current state and past excavation challenges, continues to yield invaluable data. It remains a critical nexus for understanding Late Bronze Age Cyprus—a period of dynamic interaction, economic power, and evolving social complexity at the crossroads of the Aegean, Near East, and Egypt. The examination of Enkomi's stratified remains, elaborate burials, international imports, and the earliest evidence of writing on the island provides the empirical basis for our understanding of Cypriot protohistory. Future research and continued analysis of unpublished material promise to refine our knowledge of this essential site, offering more nuanced interpretations of its rise, flourishing, and eventual transformation.