Athienou

An archaeological site in central Cyprus with a long history, known for its rural sanctuary, Late Bronze Age copper smelting, and significant sculptural finds from the ancient city of Golgoi.

History of Athienou

The archaeological site of Athienou, situated in the central Mesaoria plain of Cyprus, presents a complex stratigraphic record spanning millennia of human activity. It is a locality that has been subject to archaeological interest since the nineteenth century, yet its full significance continues to be elucidated through ongoing systematic research. For those examining the broader trajectory of Cypriot prehistory and protohistory, Athienou serves as a critical nexus, offering insights into settlement patterns, economic transformations, and cultic practices across distinct chronological horizons. Its position, mediating between the Troodos foothills and the coastal centers, rendered it a natural crossroads, attracting diverse forms of human engagement from the Middle Bronze Age through the Hellenistic and Roman periods.

Early Investigations and the Genesis of Knowledge

Initial archaeological engagements with the Athienou region were largely driven by antiquarian pursuits in the mid-to-late nineteenth century. Figures such as Luigi Palma di Cesnola, an American consul, and Edmond Duthoit, a French architect working for the Marquis de Vogüé, conducted early explorations. Cesnola initiated investigations around Athienou as early as 1867, though his early finds at the ancient city proper were not initially deemed significant. However, the area of Golgoi-Ayios Photios, east of modern Athienou, yielded substantial discoveries, including at least one colossal stone statue found before 1870. Duthoit, in 1862, explored sites southwest of Athienou, including one he termed "Malloura," from which his team recovered numerous sculptures and fragments. These early efforts, while often lacking the systematic methodologies of modern archaeology, brought to light a remarkable quantity of Cypriot art, much of which subsequently entered major museum collections, such as the Louvre and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The nature of these early investigations, characterized by a focus on art acquisition, resulted in a significant loss of contextual data. Exact findspots were often forgotten, and widespread looting by local residents became a common practice in the intervening decades. This necessitated a re-evaluation and re-identification of these historically known areas in the mid-to-late twentieth century. Paul Åström and Oliver Masson conducted brief investigations in the late 1950s and early 1960s, which helped to re-establish the probable location of the principal sanctuary near the hill of Teratsovouno. In 1961, the Cyprus Survey, under Kyriakos Nicolaou, further documented fragments of limestone sculptures and terracottas in the Ayios Photios area, but access to this zone has been restricted since 1974 due to its proximity to the "Green Line," limiting further comprehensive research.

The challenges posed by early, unsystematic excavations and subsequent disturbances underscored the necessity for a more rigorous approach. This led to the establishment of the Athienou Archaeological Project (AAP) in 1989. Initiated by Michael Toumazou, a native of Athienou, the project was compelled by the accelerating threat of agricultural activity in the valley to ancient remains. The AAP adopted an interdisciplinary framework, integrating archaeological excavation with community engagement, recognizing the importance of local knowledge and fostering a mutual relationship with the residents of Athienou.

Key Archaeological Areas and their Significance

The archaeological landscape of Athienou is primarily defined by several key areas, each offering distinct contributions to the understanding of Cypriot history:

-

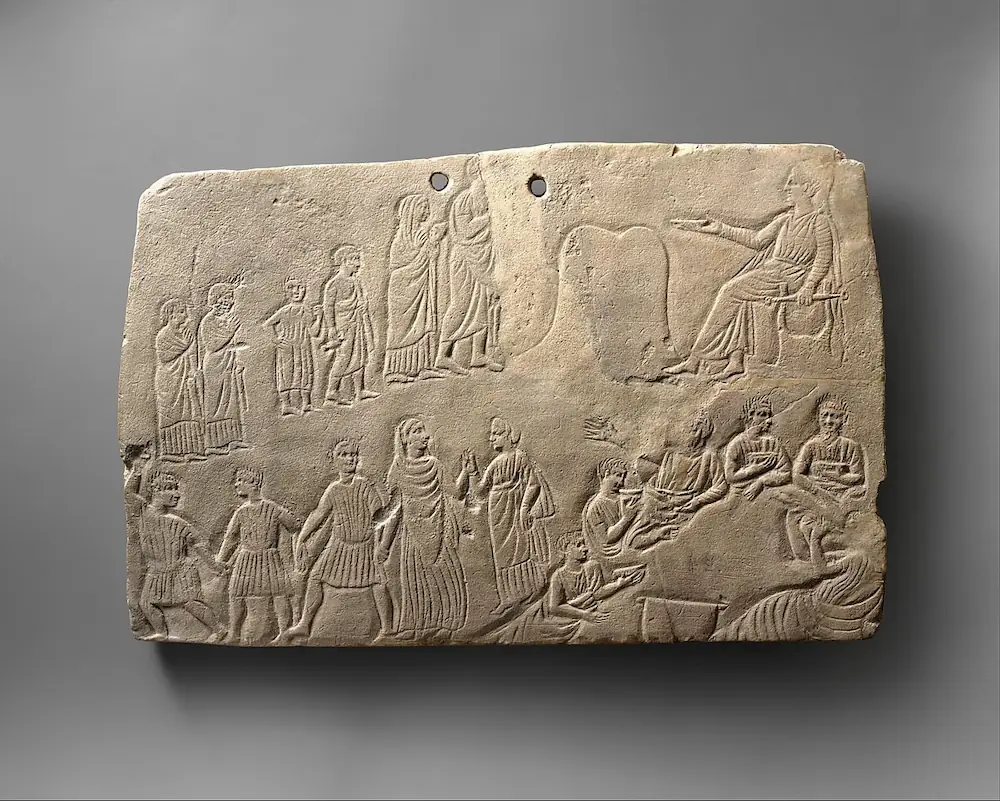

Athienou-Malloura: This site, located less than 5 km southwest of the modern town, was the focus of Duthoit's early efforts and subsequently became the primary excavation area for the Athienou Archaeological Project. Malloura is identified as an open-air, rural sanctuary with a prolonged period of use, spanning from the Cypro-Geometric III period through the Hellenistic and Roman eras. The sanctuary yielded a significant corpus of inscribed objects, alongside a rich assemblage of sculptures and terracotta figurines. The prevalence of terracotta horses and riders suggests a particular cultic focus, while stone sculptures were also abundant. The site's stratigraphy is complex, with colluvial deposits as deep as 2.5 meters covering the built remains, highlighting the impact of natural processes on preservation. The AAP's methodical excavation of the sanctuary has provided crucial data for understanding religious practices and social dynamics during the period of the Cypriot city-kingdoms. The "Stone of Athienou," referring to the local soft limestone quarries in the Idalion-Golgoi/Athienou region, which provided fine material for sculptors, suggests a local school of artistry.

-

Athienou-Ayios Photios (Golgoi): Traditionally identified as the ancient city of Golgoi, this area is located to the east of Athienou. As noted, it was a primary source for the impressive quantity of Cypriot sculpture collected by early antiquarians like Cesnola. While precise details of the ancient city itself remain somewhat elusive, the overwhelming evidence points to Golgoi as a prominent cultic center, particularly associated with the worship of Aphrodite. The region's fine soft limestone quarries were instrumental in supporting a vibrant sculptural production, evidenced by the thousands of fragments and statues found here. Its significance for understanding Archaic to Hellenistic period cults and artistic traditions on Cyprus is substantial.

-

Athienou-Pamboulari tis Koukounninas: This site, situated 200 meters north of the modern town, was excavated by Israeli teams in 1971 and 1972, following preliminary surveys by Porphyrios Dikaios and Chrysostomos Paraskeva in 1958. It represents an industrial center, primarily for copper smelting, with occupation dating from the Middle Cypriot III period, abandoned, and then reoccupied in the Late Cypriot period when copper production flourished. The presence of large pithoi (storage jars), votive vessels, and metal slag indicates significant industrial activity. The discovery of a bronze chariot model, similar to one found at Enkomi, further underscores the site's importance and potential connections within the island. Pamboulari tis Koukounninas is critical for comprehending Cyprus's role in the Late Bronze Age copper trade and its regional economic networks, given Athienou's central location between mining areas and coastal commercial hubs.

Chronological Trajectories of Occupation

The archaeological record at Athienou reveals a multi-period occupation, characterized by periods of intense activity interspersed with phases of reduced presence or apparent abandonment:

-

Middle Cypriot III - Late Cypriot I (c. 17th-15th centuries BCE): The earliest significant occupation at Athienou is evidenced at Pamboulari tis Koukounninas, dating to the Middle Cypriot III period. While the nature of this initial settlement is not fully clear, it shows no immediate signs of industrial activity or cultic objects. However, this phase precedes the major florescence of copper production, indicating a foundational presence for later industrial development.

-

Late Cypriot II - Late Cypriot III (c. 14th-11th centuries BCE): This period marks the zenith of industrial activity at Pamboulari tis Koukounninas. The site experienced a floruit in the 13th and early 12th centuries BCE, characterized by metalworking, as attested by the discovery of slag and processed ore. The pottery assemblage from this period is rich, including both local wares and imports from other regions, suggesting extensive trade networks. The site's history reflects a broader pattern of Late Bronze Age occupation in Cyprus, often including a period of prosperity followed by abandonment. For Athienou, this abandonment occurred around the mid-11th century BCE. This period also saw the introduction of new elements, possibly from the Aegean world.

-

Iron Age (Cypro-Geometric III - Cypro-Archaic, c. 9th-6th centuries BCE): After an apparent gap in occupation following the Late Bronze Age, Athienou saw renewed activity, particularly at Malloura. This reoccupation, beginning in the Cypro-Geometric III period, marks the establishment of sanctuaries that continued in use through the Archaic, Classical, and Hellenistic periods. While the early Iron Age (Cypro-Geometric I-II) is less well-attested at Athienou itself, the broader region of the Mesaoria plain, where Athienou is located, was a dynamic area of emerging city-kingdoms. The concept of a "power vacuum" following the abandonment of Late Bronze Age towns, leading to new foundations like Amathus, resonates with the re-establishment of settlements in areas like Athienou. The absence of continuous occupation from the Late Bronze Age into the Iron Age is a notable feature in some areas of Cyprus, with sites like Athienou reflecting new settlement dynamics.

-

Classical and Hellenistic Periods (c. 5th-2nd centuries BCE): The sanctuaries at Malloura and Ayios Photios continued to flourish during these periods, as evidenced by the quantity of sculptures and votive offerings. The ancient city of Golgoi (Athienou) also displays evidence of impressive remains from the Cypro-Classical period, including fortification walls, defensive towers, an acropolis, and various production and storage facilities. The discovery of a bronze statuary foundry dating to the late Hellenistic period further highlights the advanced craftsmanship and economic activity in the region during this time.

-

Roman and Early Christian Periods (c. 1st century BCE - 4th century CE): Athienou continued to be inhabited, albeit with intermittent occupation and partial rehabilitation of earlier structures. Remains from these periods are documented at Malloura and other areas, indicating a long-term, albeit sometimes less intensive, human presence.

Material Culture and Economic Insights

The archaeological finds from Athienou provide a rich corpus for understanding the material culture and economic life of its inhabitants:

-

Sculptures and Terracottas: The most iconic finds from Athienou are the abundant limestone sculptures and terracotta figurines, particularly from the sanctuaries at Malloura and Ayios Photios/Golgoi. These objects often depict cultic figures, deities, and votaries, including numerous representations of horse-and-rider figures at Malloura. The stylistic characteristics of these sculptures point to a distinct "Athienou school" of sculptors, utilizing the locally available creamy chalk limestone from the Pakna Formation. These artistic expressions provide crucial insights into Cypriot religious practices and iconography, often combining Near Eastern and Aegean influences within a local idiom.

-

Pottery: Pottery assemblages from Athienou span a wide chronological range, from Middle Cypriot III to the Iron Age and later. At Pamboulari tis Koukounninas, Late Cypriot pottery includes local fabrics and imports, reflecting regional and broader Mediterranean trade. The presence of "Proto-White Painted" sherds from the early 11th century BCE is particularly noteworthy for dating the transition into the Iron Age. While some early Iron Age material is present, the quantity of ceramics can vary significantly across periods and areas of the site, indicating different intensities and types of occupation.

-

Copper Industry: The evidence for copper smelting at Pamboulari tis Koukounninas in the Late Bronze Age is a fundamental aspect of Athienou's economic profile. The presence of copper slag, charcoal, and other industrial debris indicates that Athienou played a role in the island's renowned copper production and trade, which was a cornerstone of the Cypriot economy in the Bronze Age. This industrial activity is particularly significant given Athienou's central location, linking the copper-rich Troodos mountains to coastal centers for export.

-

Agricultural and Utilitarian Artifacts: Beyond the prominent cultic and industrial finds, Athienou has yielded artifacts reflecting daily life and agricultural practices. These include ground stone tools, stone grinding vessels, and especially threshing sledge flints. The use of threshing sledge flints, in particular, illuminates ancient agricultural technologies and their continuity over time. The prevalence of utilitarian and coarse ware vessels, such as amphorae, jugs, and large storage pithoi, at sites like Kalavasos Vounaritashi (which shares affinities with Amathusian workshops, hinting at broader regional economic patterns) indicates processing, production, and storage activities associated with agro-pastoral economies.

The Significance of Athienou

Athienou's significance extends beyond the mere cataloging of finds and chronological sequences. Modern archaeological work, particularly by the Athienou Archaeological Project, exemplifies an integrated approach that addresses both academic questions and community concerns.

-

A Crossroads and a Gateway: Athienou's geographical position in the Mesaoria plain, halfway between Nicosia and Larnaca, and historically connecting the copper mines to coastal trade hubs, makes it a crucial "crossroads" in the island's landscape. It functioned as a strategic intermediary point, facilitating trade and communication. This central location also exposed it to influences from various directions, contributing to the hybridity often observed in Cypriot material culture.

-

Continuity and Discontinuity: The site offers a nuanced perspective on settlement continuity. While some periods show clear, uninterrupted occupation, others exhibit gaps or shifts in settlement patterns. The apparent abandonment of the Late Bronze Age industrial center, followed by reoccupation in the Iron Age, speaks to larger island-wide transformations during the transition from the Bronze to Iron Ages. Investigating these patterns allows archaeologists to understand the resilience and adaptability of Cypriot societies in response to environmental, economic, and political changes. The re-use of older sites, such as the Late Bronze Age ashlar building at Maroni Vournes becoming an Archaic sanctuary, provides a comparative framework for understanding the re-appropriation of ancient spaces for new purposes, a phenomenon potentially applicable to Athienou.

-

Interdisciplinary Research and Community Engagement: The Athienou Archaeological Project's emphasis on interdisciplinary collaboration, including geoarchaeological analysis of deposits and detailed studies of artifacts, provides a more holistic understanding of the site. Furthermore, its strong integration with the local community, including public presentations, educational initiatives, and contributions to the local economy, serves as a model for how archaeological endeavors can reinforce local identity and facilitate the preservation of heritage. By acknowledging the desire of Athienou residents to connect with their past, the project fosters a dynamic dialogue between academic research and local concerns, enhancing the very sense of place for the community.

In conclusion, Athienou stands as a testament to the dynamic and interconnected history of Cyprus. From its early exploitation by antiquarians to contemporary systematic excavations, the site continues to yield fundamental insights into the island's Bronze Age industrial prowess, its enduring cultic traditions through the Iron Age and classical periods, and its strategic role as a hub in the Cypriot landscape. The ongoing research at Athienou not only addresses specific archaeological questions but also contributes to broader debates on settlement patterns, human-environment interactions, and the complexities of cultural continuity and change in the ancient Near East and Mediterranean.