Alassa

A major Late Bronze Age urban centre in Cyprus, closely linked to the island's copper production and a leading candidate for the capital of the ancient kingdom of Alashiya.

History of Alassa

The archaeological site of Alassa, located in the Limassol District of Cyprus, is an important location for understanding the island's Late Bronze Age. This inland settlement appears to have been a significant center in the region's economic networks, and it is a leading candidate for the administrative heart of the powerful yet enigmatic kingdom of Alashiya. The site itself is a complex of several areas, including Alassa-Paliotaverna and Alassa-Pano Mantilaris, which formed the main Late Cypriot settlement, and Alassa-Kampos, which contains later Iron Age burials.

Discovery and Excavation

Alassa's existence was unknown to archaeologists until 1983. It was discovered during a salvage survey conducted in advance of the Kouris dam construction, a project that would flood the valley. While such rescue archaeology can sometimes limit the scope of a dig, in this case, it led to the discovery of a major Late Cypriot settlement that might otherwise have remained hidden.

Following the discovery, The Alassa Archaeological Project was established. Under the direction of S. Hadjisavvas, excavations took place from 1984 to 2000, focusing on the Late Bronze Age sites of Pano Mantilaris and Paliotaverna. This long-term project produced the bulk of our current knowledge about the site, particularly for the Late Cypriot IIC-IIIA periods (roughly 1300-1100 BCE). The faunal remains from the excavations were also studied by P.W. Croft, providing information on the diet and animal husbandry of the inhabitants.

Geographical and Chronological Context

Alassa occupies a strategic position in the southern foothills of the Troodos Mountains. It sits at the meeting point of the Limnatis and Kyros rivers, which then flow into the larger Kouris River. Unlike many of Cyprus's famous Bronze Age centers, which were coastal, Alassa was an inland settlement. This location was no accident; it placed Alassa close to the rich sulphide ore deposits of the Troodos, the source of Cyprus's famous copper. This proximity to mineral wealth was central to its economy and influence. To date, Alassa is the only excavated Late Cypriot IIC-IIIA settlement found in the hilly piedmont of the Troodos, making it a unique window into the life of inland communities during this era.

While the settlement's peak was in the Late Bronze Age, evidence from the surrounding area, such as at Alassa Palialona, shows activity stretching back to the Middle Cypriot (c. 1900-1650 BCE) and early Late Cypriot periods. However, the main settlement at Paliotaverna and Pano Mantilaris, with its most impressive architecture, was primarily built and occupied during the 13th century BCE (Late Cypriot IIC), with some activity originating in the 14th century BCE and continuing into the 12th century BCE (Late Cypriot IIIA).

The Settlement Layout: Paliotaverna and Pano Mantilaris

The full settlement of Alassa is estimated to have covered between 7 and 12.5 hectares, making it a considerable urban center for its time. Excavations have concentrated on two main localities that show a clear functional difference.

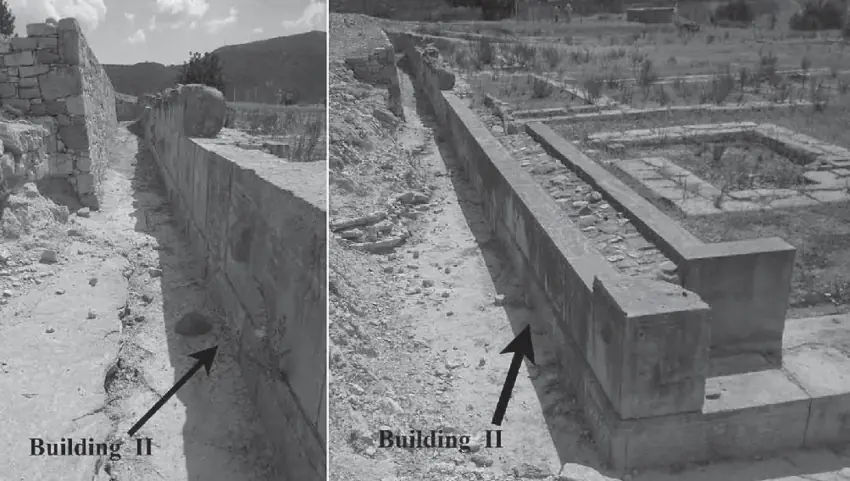

Alassa-Paliotaverna is defined by its monumental architecture. Here, archaeologists uncovered buildings constructed with impressive ashlar masonry—large, carefully cut and dressed stone blocks. This type of construction was expensive and labor-intensive, and in Late Bronze Age Cyprus, it is almost always associated with high-status buildings, such as administrative centers, palaces, or religious sanctuaries. The main construction at Paliotaverna dates to the 13th century BCE and points to this area being the public or elite quarter of the settlement.

Alassa-Pano Mantilaris, by contrast, appears to have been a densely populated residential area. The architecture consists of domestic quarters alongside various specialized installations for crafts and household production. The layout suggests a well-organized community living and working in close quarters.

This division between the monumental, administrative buildings at Paliotaverna and the domestic-industrial zone at Pano Mantilaris suggests a complex and organized society. While large-scale metalworking workshops have not been found directly within the excavated areas, the site's location makes it clear that control over the copper industry was its primary function. Alassa likely served as an administrative center that oversaw the mining, initial processing, and transport of copper from the mountains down towards the coast for export.

The Alashiya Connection

One of the most debated questions in Bronze Age archaeology is the location of Alashiya. This kingdom is frequently mentioned in ancient texts from the Near East, especially in the diplomatic archives found at El-Amarna in Egypt and the ancient city of Ugarit in Syria. These cuneiform tablets, dating to the 14th and 13th centuries BCE, describe Alashiya as a major political power and, most importantly, as a primary supplier of copper to the great empires of the day. The texts make it clear Alashiya was a kingdom on an island, and for decades, scholars have equated Alashiya with all or part of Cyprus.

For a long time, the exact location of Alashiya's capital within Cyprus remained a mystery. A breakthrough came from scientific analysis of the clay tablets themselves. Using petrographic and chemical analysis—methods that examine the microscopic mineral composition of the clay—researchers were able to trace the geological origin of the material used to create the Alashiya letters. The results showed that the clay was not sourced from a coastal location, as many had assumed, but from the southeastern foothills of the Troodos Mountains. Since ancient scribes typically sourced their clay locally, this provided a strong indication that the administrative heart of Alashiya was located in this specific inland region.

Within this geological zone, Alassa is one of the primary candidates, along with the nearby site of Kalavasos-Ayios Dhimitrios. The geology around Alassa is a perfect match for the clay used in some of the Amarna letters, particularly a tablet known as EA 37. Some researchers also point to the phonetic similarity between the ancient name Alashiya and the modern village name Alassa, suggesting a linguistic echo that has survived for over three thousand years. While this cannot be proof on its own, the convergence of textual, geological, and archaeological evidence makes a compelling case. Alassa, with its monumental administrative buildings and strategic control over the Kouris river valley—a valley that flourished during Alashiya's ascendancy—is now considered by many to be the most likely candidate for the capital of this powerful Bronze Age kingdom.

Economy and Regional Trade

Alassa's inland location defined its economic role. It was part of a regional system where different sites performed specialized functions. Scholars propose that inland centers like Alassa and Kalavasos-Ayios Dhimitrios acted as primary administrative hubs, controlling the copper mines and the flow of metal. They would have managed the production and then transported the copper to coastal partners for international shipment.

The coastal site of Episkopi-Bamboula has been identified as a likely partner for Alassa, serving as its gateway to maritime trade routes. Interestingly, excavations at Episkopi-Bamboula have yielded a greater quantity of imported luxury goods than Alassa. This is not surprising if Alassa's main role was administrative and industrial, while its coastal port handled the direct exchange of goods with foreign merchants.

The pottery found at Alassa also helps reconstruct its economic life. Large storage jars known as pithoi, some of which may have been imported, were used to store and transport commodities. While Alassa has yielded few imported Mycenaean goods compared to coastal sites, the presence of two Mycenaean stirrup jars at Pano Mantilaris confirms that it was connected, even if indirectly, to the wider Aegean trade network. More common pottery types, like specific hemispherical bowls, show strong similarities to ceramics found at other major Cypriot centers like Kition and Episkopi-Bamboula, indicating shared cultural traditions and robust regional interaction.

Architecture and Urban Scale

The use of ashlar masonry at Paliotaverna is a key indicator of Alassa's status. This building technique, involving precisely cut stone blocks laid in regular courses, requires significant resources, skilled labor, and strong central organization. Its appearance in Late Bronze Age Cyprus is often seen as a reflection of a strong political authority. The style is not Aegean but shows closer parallels to building traditions in the Levant (modern-day Syria and Lebanon), highlighting Cyprus's strong connections to the Near East. The presence of such monumental structures at an inland site like Alassa reinforces its role as a primary urban and administrative center, capable of commanding the wealth and manpower needed for such projects. The settlement's large estimated size of up to 12.5 hectares further confirms that it was one of the major population centers on the island during its time.

Later Occupation

The Late Bronze Age was Alassa's zenith, but human activity in the area did not cease with the decline of its copper-focused economy. At Alassa-Kampos, a separate locality from the main Bronze Age settlement, archaeologists have excavated two tombs from the Cypro-Archaic I period (c. 750-600 BCE). This discovery shows that the area remained inhabited, or at least was used for burials, well into the Iron Age. This pattern of shifting settlement focus is common in Cyprus, as political and economic changes across the centuries led to the decline of old centers and the rise of new ones. The finds at Alassa-Kampos demonstrate a continuity of human presence, even after the great Bronze Age town had passed its peak.