Navigating the Grey: The UNESCO 1970 Convention and the Ethics Antiquities Collections

Alexis Drakopoulos

Alexis Drakopoulos is a Greek Cypriot Machine Learning Engineer working in Financial Crimes. He is passionate about Archeology and making it accessible to everyone. About Me.

This article explores the landmark 1970 UNESCO Convention, the international law designed to halt the illicit trade of cultural heritage. We examine its real-world complexities through the unique case of Cyprus, where a long history of legal exports collides with the tragedy of looting, forcing a nuanced approach to ethical collecting.

March 15, 2025

Discussion

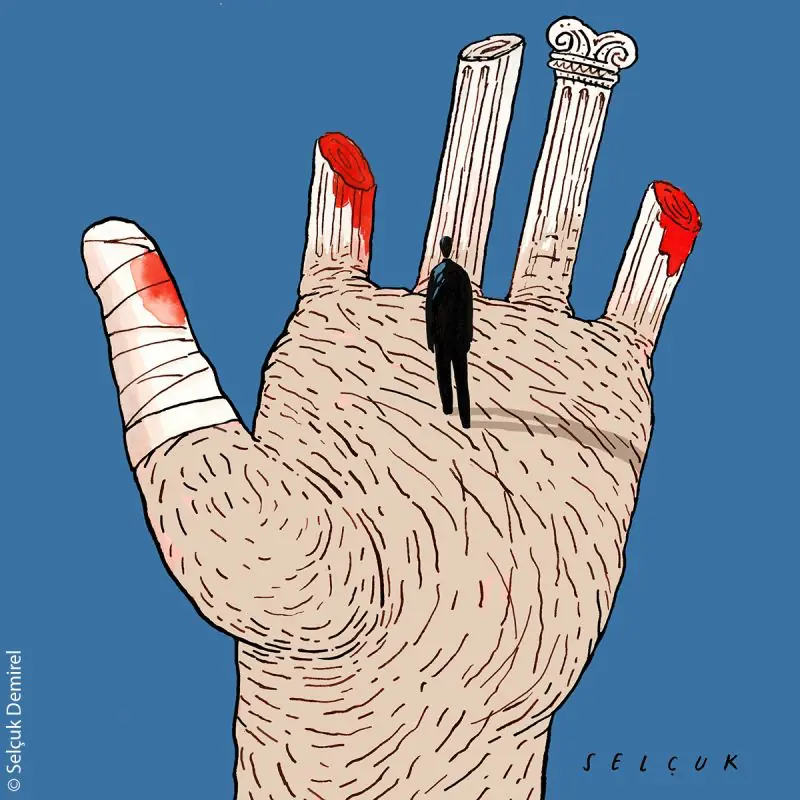

The era of treasure hunting, when antiquities were collected as trophies of travel or conquest, is long past. Modern archaeology operates on a fundamental principle: an object’s primary value is not aesthetic, but contextual. An artifact illegally ripped from the earth is an object stripped of its story. Its relationship to other objects, to the layers of soil, to architectural remains, all the data that allows us to reconstruct the past, is irrevocably destroyed. A pot often just becomes a pot, its ability to inform on trade, diet, or ritual practice severely diminished. This destruction of provenance is the fundamental damage caused by illicit excavation, transforming a piece of history into a mere commodity.

This practice may fuel an illicit market, and in many archaeologically rich countries, systematic looting remains a persistent and corrosive force. The situation in Cyprus, however, presents a more nuanced picture. While the island suffered a catastrophic wave of plundering following the political upheaval of the 1974 invasion, it has not been subjected to the kind of continuous, commercially driven looting seen elsewhere. There is little evidence of such systematic activity in modern-day Cyprus.

This specific context makes the ethical responsibility of today's institutions all the more critical. The primary imperative is to ensure that no object derived from looting, particularly from the post-1974 period, ever enters the legitimate art market or other collections. It is critical that any artifact suspected of having such an origin be considered untouchable. If an object's illicit past is identified, it must be reported to the Cypriot Department of Antiquities for repatriation. There can be no compromise on this point.

It is within this framework of lost context and ethical responsibility that the 1970 UNESCO Convention must be understood. Formally titled the Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property, this international agreement was designed to provide a legal and ethical line against the ongoing pillage of cultural heritage. It established a chronological threshold that separates the acquisitions of the past from the obligations of the present. Yet, the convention’s direct application is not always simple, especially in a case like Cyprus with its distinct history of legal export followed by concentrated, event-driven looting.

Let's explore the UNESCO 1970 Convention as a practical, and often challenging, guide for ethical stewardship. We will examine its provisions and the historical context that made them necessary. We will then focus on the specific case of Cyprus, using the Drakopoulos Collection as a case study to investigate the meticulous due diligence required to build a responsible collection today. This analysis aims to show that while the convention is an imperfect tool, its principles have rightly forced a level of accountability that is essential for the preservation of our shared past.

Part I: The Letter of the Law – Understanding the UNESCO 1970 Convention

The mid-twentieth century witnessed an escalation in the looting of archaeological sites and the trafficking of cultural objects. Buoyed by a rising art market and increased global mobility, artifacts moved from archaeologically rich but economically developing nations to the auction houses and museums of Europe and North America. In response to this growing crisis, the international community, through the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), drafted the 1970 Convention.

Its formal title is long but descriptive: The Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property. Its purpose was not to retroactively punish the colonial era removals of the 18th and 19th centuries, such as the Elgin Marbles from Greece or the Rosetta Stone from Egypt. The drafters recognized that litigating the past was a fraught and perhaps impossible task. Instead, the convention’s focus was on the future. Its primary goal was to create an international legal framework to stop the ongoing pillage of cultural heritage.

The core principles of the convention are straightforward. Signatory nations, or "State Parties," agree to implement a series of measures within their own borders. These include creating national inventories of protected cultural property, establishing systems of export certificates, and controlling archaeological excavations to prevent clandestine digging. States pledge to actively oppose the illicit import and export of cultural items and to facilitate the recovery and return of stolen property.

The most consequential provision of the convention, and the one that has had the most profound impact on museums and collectors, is the establishment of the year 1970 as a chronological benchmark. For an institution or individual adhering to the spirit and letter of the convention, any cultural object that does not have a documented provenance showing it was outside its country of origin before 1970, or that it was legally exported after 1970, is treated as presumptively illicit. This simple date created a new ethical standard. Before its adoption, many museums and collectors operated under a principle of "buyer beware," where the legal title was the primary concern. After 1970, the ethical burden shifted. The new standard required a "good faith" purchaser to perform due diligence not just on legal title, but on the object’s entire ownership and export history.

The convention, however, is not self-enforcing. It relies on the domestic laws and political will of its signatory states. A country must ratify the convention and then pass its own national legislation to give it legal force. The United States, for example, ratified the convention in 1972 but did not pass the implementing legislation, the Convention on Cultural Property Implementation Act (CCPIA), until 1983. This time lag, common in many countries, created a period where the international standard existed but lacked domestic legal teeth. Furthermore, the convention’s power is primarily preventative. While it provides a framework for repatriation claims, the legal processes are often slow, expensive, and dependent on robust cooperation between nations. Its greatest strength has been its moral and ethical force, which has reshaped the acquisition policies of every major museum in the world and established the vocabulary for our modern debate on cultural heritage.

Part II: The Cypriot Context – A Unique Provenance Landscape

To understand the challenges of applying the UNESCO 1970 Convention to Cypriot antiquities, one must first understand the island’s unique archaeological history. Unlike Egypt or Mesopotamia, where systematic, profit-driven looting for a hungry export market has been a persistent problem for centuries, Cyprus presents a different picture. The story of Cypriot artifacts on the international market is largely a tale of two distinct eras: the period of legal, often state-sanctioned export, and the catastrophic looting that followed a specific political event.

From the 19th century through the late-1970s, the export of Cypriot antiquities was not only possible but common. During the British colonial period (1878-1960), archaeological expeditions were undertaken by foreign institutions, and a system known as partage was often in effect. Under this system, a portion of the excavated finds was granted to the excavating institution for study and display abroad, while the remainder stayed in Cyprus. The most famous, and controversial, early figure was Luigi Palma di Cesnola, an American consul who, in the 1860s and 1870s, amassed a colossal collection of Cypriot antiquities through extensive, unscientific excavations. While his methods are condemned by modern standards, his actions were conducted under the authority of the then-ruling Ottoman government. His collection, which formed the foundation of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Cypriot holdings, left the island legally. We estimate that over 110,000 objects were legally exported from Cyprus in total.

After Cyprus gained independence in 1960, the new Republic of Cyprus continued to regulate the trade in antiquities. The Department of Antiquities oversaw a system where certain common types of artifacts could be legally sold and exported. It was not unusual for tourists visiting the island in the 1960s and early 1970s to purchase a small collection of genuine Roman glass or Iron Age pottery from a licensed dealer and receive an official export license from the government. These objects, though now outside Cyprus, left the island with the full permission of the state. Their provenance is legitimate.

This landscape of regulated trade was shattered in July 1974. The Turkish invasion of Cyprus and the subsequent division of the island created a humanitarian and political crisis. It also precipitated an archaeological catastrophe. The northern part of the island, now under Turkish military control and inaccessible to the Republic of Cyprus’s authorities, became a fertile ground for looting. Churches and monasteries were systematically stripped of their Byzantine icons and frescoes. Archaeological storerooms were broken into. Ancient cemeteries and settlement sites, left unguarded, were plundered.

This post-1974 looting was of a different character than anything that had come before. It was targeted, extensive, and its products were fed either into Northern occupied museums or to the art market. Notorious cases, such as the theft of the Kanakaria mosaics, illustrate the scale of the problem. These 6th-century masterpieces were pried from a church wall in the Lythrangomi village and eventually surfaced for sale in the United States, leading to a landmark legal case that resulted in their return to the Church of Cyprus. This period of intense, concentrated looting is the primary source of truly illicit Cypriot antiquities on the market today.

This history creates a crucial distinction. An undocumented Cypriot object is not automatically a looted object. One must ask a more specific question: what kind of object is it? A collection of common Red Polished Ware from the Early Bronze Age or simple Roman glass vessels is far more likely to have originated from the old, legal trade than from the targeted, or post-1974 plunder.

Furthemore, the economic reality of the antiquities market plays a significant role. Cypriot antiquities, particularly pottery, have a low market value compared to other ancient cultures. A fine Attic red-figure vase or an Egyptian sarcophagus can command tens of thousands or hundreds of thousands of dollars. A typical Cypriot Iron Age amphora, by contrast, might sell for a few hundred. This economic fact means that there has never been a sustained, large-scale, profit-driven looting industry in Cyprus in the same way there has been in places like Egypt, Italy, or Cambodia. The risk and effort of clandestine excavation simply do not yield a positive financial return. The looting that did occur was overwhelmingly opportunistic, driven by the unique chaos of the 1974 invasion, or by locals opportunistically looting tombs and active dig sites. This context is essential when evaluating the likely provenance of a Cypriot object that appears on the market today.

Part III: The Practice of Acquisition – Beyond Black and White

The UNESCO 1970 Convention provides a date, but reality provides nuance. The work of an ethical curator or collector begins where the simple application of the rule ends. It requires a process of rigorous due diligence that moves beyond documents and into the realm of critical judgment, historical context, and human motivation. This is where the complexities of the convention become most apparent.

For decades following 1970, many institutions adopted a passive approach. The lack of a pre-1970 provenance was not necessarily a barrier to acquisition, especially if the object was highly desirable. Some curators operated under a "don't ask, don't tell" policy. If an object was offered by a reputable dealer and there was no active claim against it, it might be acquired. The ethical calculus often tilted in favor of the museum’s mission to build a comprehensive collection. The argument was sometimes made that by acquiring an object, even one with a cloudy history, the museum was "rescuing" it for public study and preservation.

This attitude has recently become untenable. The global consensus, driven by the persistent advocacy of source countries and archaeological organizations, has shifted. Today, major museums will usually not acquire an object without a documented, verifiable provenance stretching back to before 1970 or proof of legal export. This creates its own set of challenges.

This is where the practice of acquisition becomes an exercise in judging evidence. Consider a common scenario: an institution is offered a small group of Cypriot ceramics by the daughter of an elderly woman who has recently passed away. The daughter explains that her mother, a British schoolteacher, bought the pieces while on holiday in Cyprus in 1968. She has no receipt or export license—these were lost long ago—but she has holiday photographs from the trip and remembers her mother telling the story for fifty years. The objects themselves are typical of the kind sold in tourist shops at the time: a few small amphorae, a bowl, and a juglet. They are not museum-quality masterpieces.

How does one assess this? The 1970 rule, applied rigidly, would disqualify these objects. There is no hard documentation. Yet, a contextual approach suggests a different conclusion. The story is highly plausible and fits the known patterns of legal trade in Cyprus during that period. The objects themselves align with the story; they are not the type of material associated with the post-1974 looting. The seller has no obvious incentive to invent a complex lie for items of modest value. In this case, a responsible curator might make an informed decision that, on the balance of probabilities, the objects have a clean history. These objects can further be checked with the Department of Antiquities to validate they are not on stolen object lists. This is not "bending the rules," but engaging in the kind of nuanced analysis that the convention, in its practical application, requires.

The assessment changes dramatically if the circumstances differ. If the same objects are offered by a dealer known to have handled illicit materials in the past, the level of skepticism must be higher. If the collection includes a rare piece of Bronze Age statuary or a fragment of a Byzantine fresco, the seller's story becomes far less credible, as such items were rarely, if ever, available on the open tourist market. One must always ask: who is the owner? What is their story? Does the evidence, both physical and narrative, support that story? Are there intermediaries involved, and what is their reputation? What are the incentives for truth or deception?

This process is critical. It acknowledges that provenance is not always recorded on paper. Sometimes it exists in family histories, in the typology of the objects themselves, and in a deep understanding of the historical context of the source country. It is an imperfect science, reliant on judgment, but it is a necessary one for institutions seeking to build an ethical collection in a world of incomplete information.

Part IV: A Case Study – The Drakopoulos Collection

Navigating this complex ethical terrain is the central challenge for any private collector committed to responsible stewardship. The Drakopoulos Collection, which now comprises over 125 ancient Cypriot objects, was assembled with these principles at its core. The collection’s primary goal is to preserve and study a representative sample of Cypriot material culture, with an unwavering commitment to ethical acquisition. This commitment has shaped every decision and has led to a collection built on a foundation of verifiable provenance.

Of the more than 125 artifacts in the collection, over one hundred have a provenance that fully complies with the strictest interpretation of the UNESCO 1970 Convention. This means they are accompanied by one of three forms of evidence. The first is an original, government-issued export license from Cyprus. These documents, typically from the 1960s or early 1970s, are irrefutable proof that the object left the island legally. The second is a documented collection history showing the object was in a collection outside Cyprus well before 1970. This can be in the form of old collection inventories, dated photographs, or publications. The third is a verifiable sale record from a reputable auction house, dealer, or previous collector that predates 1970. For these one hundred-plus objects, there is no ambiguity. Their journey into the international sphere is documented and legitimate.

The remaining items in the collection, a smaller group of around two dozen objects, occupy the "grey area" so common in the world of Cypriot antiquities. These are objects that lack definitive pre-1970 documentation but, based on a careful, multi-faceted analysis, are judged to have most likely been exported legally. The assessment for each of these pieces follows the rigorous due diligence process described earlier. It considers the object’s typology, is it a common type known to have been sold legally, or a rare type associated with looting? It considers its "collection history", was it part of an old family collection assembled in the 1950s and 60s, even if the paperwork is lost? It considers the credibility of the seller and the narrative provided.

Every object is registered with the Department of Antiquities in Cyprus and checked against their records.

A careful, case-by-case approach is essential, but it must be paired with an uncompromising red line. The Drakopoulos Collection operates under a strict and absolute policy regarding illicit artifacts. Any object that is suspected of having been looted, particularly in the post-1974 period, is not considered for acquisition under any circumstances and is immediately reported to the Department of Antiquities. Furthermore, if any object currently in the collection were ever found, through new information, to have a provenance linked to looting, it would be immediately and unconditionally repatriated to the Republic of Cyprus. This is not a passive policy but an active one, pursued in open collaboration with the Cypriot Department of Antiquities. The goal is not simply to own objects, but to be a responsible steward of cultural heritage, and that responsibility includes correcting past wrongs, should they come to light.

Part V: The Limitations and Legacies of UNESCO 1970

Fifty years after its adoption, the UNESCO 1970 Convention has a powerful and complex legacy. Its successes are undeniable. It fundamentally altered the ethical landscape of the art and antiquities world. It provided source countries with a legal tool to challenge the illicit trade and has been the basis for thousands of successful repatriation claims. Major museums have transformed their acquisition policies, moving from a position of passive acceptance to one of demanding, proactive due diligence. The convention stigmatized looting and created a global consensus that cultural heritage is not a mere commodity, but the finite and irreplaceable patrimony of all humanity. Without it, the hemorrhaging of archaeological material from source countries may have been far worse than it is today.

However, the convention is not without its limitations and unintended consequences. By establishing a rigid 1970 date, it has created a class of "orphaned" objects. These are artifacts with no documented provenance that, because of the strict policies of museums, can never be acquired for public display or study. An important historical object might sit in a private collection, unseen by scholars and the public, because its pre-1970 history cannot be definitively proven, even if all contextual evidence suggests it is not a product of recent looting. In these cases, the fear of acquiring a looted object leads to a situation where a legitimate piece of history is effectively lost to the world.

This problem is especially acute for Cypriot antiquities due to the nature of the legal export system that existed for decades. The export of antiquities from Cyprus before the mid-1970s was large and widespread, but the associated documentation was often cursory. Surviving export licenses issued by the authorities at the time frequently lack photographic records or detailed descriptions. A license might simply state "one bichrome jug," "two lamps," or "a collection of ancient pottery." For an object that has been separated from this paperwork for fifty years, it is often impossible to definitively reconnect it with its original license. This documentary gap means that for a significant portion of legally exported Cypriot material, a rigid demand for verifiable paperwork is a demand for the impossible. It necessitates a more nuanced, context-based approach that accepts the limitations of the historical record.

This challenge is compounded by simple human behavior. The average tourist or expatriate resident who legally purchased a few ceramic pieces in Nicosia or Kyrenia in 1968 had no understanding of future antiquities laws. They were not archivists or legal scholars; they were ordinary people who bought a souvenir of their time on the island and saw no reason to preserve a simple receipt or government form for half a century. Consequently, a curator or collector today is often left with a narrative, not a document. The task becomes one of critical assessment: Is the seller's story plausible? Does it align with what we know about the legal market at the time? And, crucially, what incentive might they have to lie, particularly for objects of modest financial value? Evaluating the credibility of a personal history becomes a necessary, if subjective, part of the due diligence process.

Furthermore, the convention’s effectiveness is entirely dependent on the enforcement capacity and political will of its signatories. In countries where corruption is rife or where the illicit trade is controlled by powerful criminal networks, the convention’s principles can be difficult to enforce on the ground. It is a framework for cooperation between responsible states, not a panacea for global crime. In the specific context of Cyprus, the 1970 date remains a blunt instrument for a problem that is so sharply defined by the events of 1974. The convention treats an object that left Cyprus without a license in 1971 the same as one looted from a church in 1975. While both are technically illicit, the historical and moral weight of the two acts is vastly different.

Despite these limitations, the positive legacy of the convention outweighs its flaws. It forced the world of collecting, both public and private, to confront its own complicity in the destruction of archaeological sites. It established the principle that an object’s value is not just aesthetic or financial, but also informational, and that this informational value is destroyed when it is ripped from its context by looters. It created the very ethical standard by which collections like the Drakopoulos Collection are now judged, and by which they judge themselves.

Conclusion: Toward a More Nuanced Future

The UNESCO 1970 Convention was a product of its time, a bold response to a crisis of cultural plunder. It remains the single most important instrument in the global effort to protect cultural heritage. Its principles have rightly become the foundation of ethical collecting. Yet, as we have seen, particularly through the lens of Cypriot antiquities, its application is not a simple matter of checking dates on a document. It demands a deep engagement with history, a critical evaluation of evidence, and an unwavering ethical commitment.

The journey of a Cypriot artifact from the ancient world to a modern collection is fraught with potential pitfalls. The line between a legally exported tourist souvenir from 1968 and a piece looted during the tragedy of 1974 is the fundamental ethical divide. To walk this line responsibly requires more than just adherence to a date; it requires a commitment to the convention’s underlying purpose, which is to render the act of looting pointless by eliminating the market for its products.

This means that collectors and institutions have a dual responsibility. First, they must conduct the most rigorous due diligence possible, using every available tooll; documentary, typological, and narrative, to ensure the clean provenance of the objects they acquire. Second, they must maintain an open and collaborative relationship with source countries. The policy of the Drakopoulos Collection to immediately repatriate any object found to have a tainted past, in direct partnership with the Cypriot Department of Antiquities, is a model for this responsibility in action.

The future of cultural heritage protection will require an evolution of our approach. We must continue to refine the tools provided by the 1970 Convention, perhaps finding ways to address the issue of "orphaned" objects without creating loopholes for the illicit trade. Greater investment in the protection of sites on the ground in source countries, coupled with enhanced international law enforcement cooperation, is essential. The ultimate goal is a world where the story of an ancient object is one of discovery and preservation, not one of destruction and loss. The UNESCO Convention was the first great step on that path. The diligent, ethical, and self-critical work of today’s archaeologists, curators, and collectors is the next.